The Melancholy of James Ryerson

Kays

Those of us who read history these days,

and I doubt that there are many, are drawn to stories of the pioneers who set

out courageously, defying all odds to conquer an untamed land. Their indomitable spirits overcame all

hardships; disease, Indian attacks, blizzards and plagues of locusts that would

have crushed Pharaoh. That is the story

we hear, but what is the truth? From my

reading of the stories of those men and women of yore, they seem just like

us. They had the same fears, the same

passions, and the same reactions when overwhelmed by misfortune and loss. Take for example, the “Memories of James

Ryerson Kays”, who was born in Pennsylvania in 1835, and came with his parents

to Platteville in 1849. We have a

partial copy at the museum, and the Wisconsin State Historical Society has a

full copy of the unpublished document. He

wrote his story in the manner of a man of common language and modest education. His spelling, like that of many of his

contemporaries, was atrocious. In that

we see another similarity with today’s younger folks, whose skins are saved

only by the spell checkers on their word processors.

Kays writes first of his youth, spent on

various farms in Ohio and Pennsylvania.

He describes making maple syrup and sugar, going to fairs, and orchards

full of fruit free for the taking. He

writes frankly of his youthful misdeeds with a friend: “ Once he and I sliped a way and went to a Peach

Orchard when the Peaches was ripe and we eat Peaches to our harts content and

we could have all the Peaches we wanted without stealing them but they tasted

better when you could steal them.” His life

back east as he recalled it was very good, with friends and relatives all

about. This came to an end in 1849 when

his father was convinced to move to the “far a way west” by his sister, Martha

Neely who had emigrated to Platteville, Wisconsin earlier with her husband John. The parting with family was not easy:

“and now my father having everything ready

we must make a start and the time had come to bid my mothers People a last

goodby, And it proved to be the last

goodby for the most of our Family. Did

you ever get ready to start any place in a Prairie Schooner and the time had

come to start and your Relatives and Friends had come to see you off And you

must say gooby. Did you feel that big

lump come up in your throat and that big tear run down your cheek and when you

tried to say gooby you couldent say it.

Well if you did not you don’t know what it is to part with Loved ones.”

They drove their wagon to the

small town of Cleveland, Ohio and took a ship to the even smaller town of

Milwaukee, where they disembarked and started west across the state of Wisconsin. “We followed the

Emegrant road a cross the great Prairie country and traveled miles and miles

without seeing a house…we made pretty good time and crossed the Rock River at

Janesville Wis…On this trip a cross the western Wild we seen and hurd many new

and strange things…We had never seen so much Grass and so little Timber until

we got into Wisconsin.” Soon

they were in Platteville and reunited with his father’s sister.

The Cholera epidemic of 1850 changed his

life. James and his father helped to

bury a man named Feathers, who had come from St. Louis to visit a local family. He had contracted the disease, which started

with stomach cramps, and died in a short time.

He wrote:

“the

next one to die with Cholera was my brother Martin…on Saturday morning my

brother in law come after me for my Brother Martin was dying and he said we

would have to hurry for the doctor said he had the Cholera and could not live

very long. I can see my brother as he

sat up in the Bed shakeing hands with all the rest of the Family and biding

them good by. I was the last one to take

his hand in death he bade me good By and layed down and was gone his eyes

closed in Death with no signs of anguish or pain, just Good by Good by GOOD

by.”

His mental pain was not over. On the following Wednesday his sister

Maryann, who was his mother’s favorite, began cramping at about eight in the

evening. That morning she had been fine

and “full of mischief.” On seeing her

daughter ill, his mother came down with the same symptoms. The killer worked quickly. By ten o’clock that same night, both were

dead. They were buried next to Martin. The following Sunday his father was stricken:

“He must have suffered teribly for 2 or 3 hours and

then he seemed to get better then he said he guessed it was all over now, but I

took the rong meaning to what he said I

thot he ment he would get well. But my

hopes was soon turned to sorrow for he took my hand and said goodby my Boy and

then quietly and peasfully passed a way…shortly after, Little Emma Alvira Died

Mothers Grave and Coffin was opened and she was laid on her Mothers Brest.”

He and his four younger brothers were

farmed out to area families. All but

James were too young to live alone or support themselves. “What could I

do”

he wrote, “for after Father and Mother died

I did not care where I went or where I stayed and I told them so.” Mental Depression was poorly understood then. The persistent sadness, feelings of emptiness

and hopelessness, exhaustion, restlessness and irritability were given the

broad term “Melancholy” of which “Depressing Passions” was one variety, Mania

being the other. It was felt by most

authorities of the day that this malady had its origin in the body, perhaps in

an overabundance of black bile. Nasty

purging and bloodletting were often prescribed. In 1809, Dr. John Haslam, one

of the more enlightened physicians of his time described depression thusly:

“Those under the influence of the depressing

passions, will exhibit a different train of symptoms. The countenance wears an

anxious and gloomy aspect, and they are little disposed to speak. They retire

from the company of those with whom they had formerly associated, seclude

themselves in obscure places, or lie in bed the greatest part of their time.

Frequently they will keep their eyes fixed to some object for hours together,

or continue them an equal time "bent on vacuity." They next become

fearful, and conceive a thousand fancies: often recur to some immoral act which

they have committed, or imagine themselves guilty of crimes which they never

perpetrated: believe that God has abandoned them, and, with trembling, await

his punishment. Frequently they become desperate, and endeavour by their own

hands to terminate an existence, which appears to be an afflicting and hateful

incumbrance. “

“I stayed” he wrote “and helped Uncle John Neely to finish cutting our

grain But I wasn’t much good. I could

not set myself to work. It seemed to me

that there was something the matter with me.

I could feel sore spots all over my boddy and I could not work what I

had to work for - anyway it all looked dark to me.” He was

examined by a doctor who told him he had to quit eating green corn or he might

get Cholera. Such was the medical

knowledge of the typical frontier doctor. “I

told him I didn’t care what I got. He said I had better take a dose of salts (laxative) but I did not take any salts…” Since

Cholera is a disease of the intestinal lining that causes massive dehydration

through diarrhea, a laxative would be the worst thing to take. The medical

treatment of the time called for withholding fluids. We now know that maintaining hydration is the

most essential thing in the treatment of Cholera. He tried field work for

others who told him he was “no good.” This continued into 1852; “I went to work for a farmer by the name of

Utt. I worked for him untill about the

first of June then he said I was no good and turned me off.”

So what happened to James

Ryerson Kays? He eventually found his

calling as a blacksmith, a profession he followed into his seventies. He moved to Washburn (now Arthur) and worked there

for many years as a blacksmith. His four

younger brothers joined the Union Army during the Civil War. One, George, lost a leg in the war. James was rejected

for service due to a rupture and rheumatism. Slowly he regained an enjoyment for life. He married.

He sought entertainment, writing “Our

principal Amusement was going to Dances or Balls, Fourth of July celebrations,

and once in a while a Circus. We went to one circus in Platteville where we seen Tom Thumb and his Wife, they were Dwarfs, And

a Man that could write better with his Toes than I can with my fingers. In

those days we didn’t know anything a bout the Grizzly Bear dance nor the Tango

dance nor the Bunny Hug and such fancy dances as we hear of now days.” He regained his wry sense of humor. Among his activities was attending religious

revival meetings: “We had the Old Shouting Methodist Camp Meetings

where everybody went, Even the Harlot Gamblers and Thieves was ever present at

these Camp Meetings. It was more of a

place of Amusement than a place of Worship.”

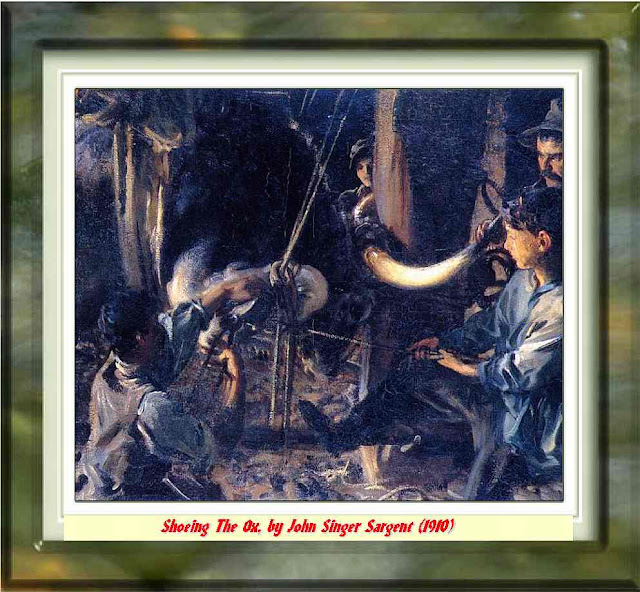

In October of 1865, he moved with his wife and three daughters to

Independence Iowa, where he continued his trade, shoeing the oxen of the

thousands moving through Iowa to the new frontiers in the far west. Later he worked for race tracks in Eastern

Iowa, shoeing the horses. By 1929 he was

95 years old and living with his daughter in Waterloo, Iowa. At that time his four younger brothers were

still living, ranging in age from 81 to 87.

Kays lived to be 100 years old. His100th

birthday was on January 4, 1935, and a local newspaper reporter paid a visit

for an interview. By that time all of

his younger brothers but George had passed away. The reporter asked him how to live to be

100. He said; “Be moderate in all things. Abstain from hard liquor and tobacco. Recognize 9 p.m. as bedtime. Keep abreast of the world and its events.” Perhaps

the reporter should have asked him the secret of happiness, for what was taken

from him in his youth was returned in family, and health, and a long life. He died 15 days after attaining the century

mark, and crossed the river to meet his family and friends who had gone so long

ago.

No comments:

Post a Comment